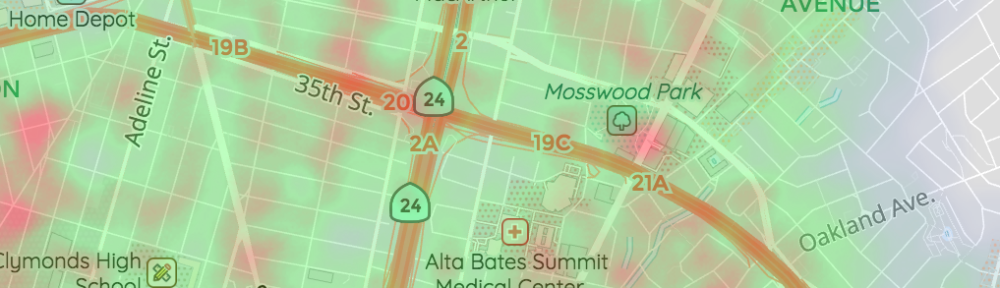

Because many people seem thirsty for data about crime and policing in their local neighborhoods, a comparable number of web services and apps have recently emerged. The simplest of these get their data from police departments (somehow, see below), then narrow them to a region very close to the person’s phone, and plots those incidents on a map.

Imagine you are using one of these apps, and know of an incident that has happened a few blocks from your home. You might click on it to find more information, for example when it happened, the type of crime (break-in, assault, armed robbery, …) reported, and perhaps an incident number that allows you to communicate with your local police department about it. Perhaps the location or time/date listed seems incorrect based on what you know. Or, imagine that you know of an incident that happened in your neighborhood but which is not shown on this map. In this case, you may want to communicate with your neighbors, or your police department, about the circumstances that concern you.

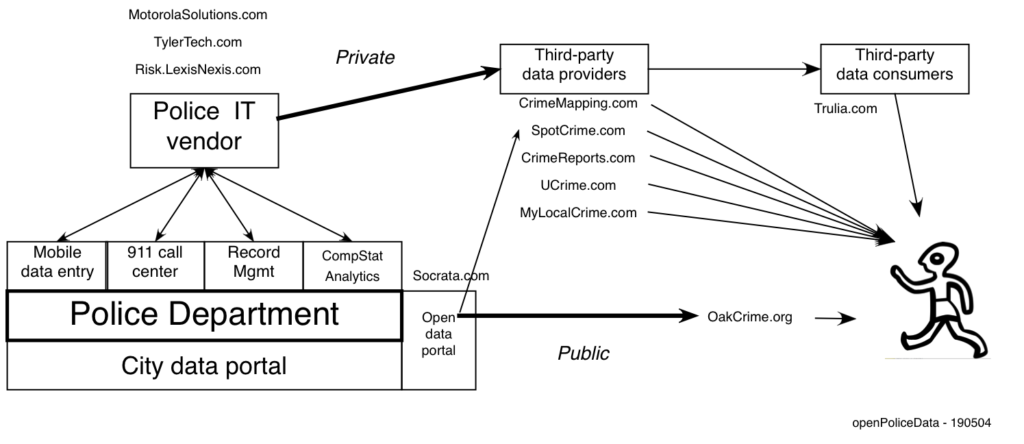

In all these cases, you want to be able to get more specifics: how does the data on your phone get there from your police department? The short answer is by one of two routes, as sketched in Figure 1: either 1) the police department has released the data directly to the public; or 2) a vendor of police information technology (IT) used by the police department provides access to it for others.

Public police data

Many progressive police departments have made commitments to publish their data, in a redacted form for access by the public. The goal is to support increased mutual trust through transparent data exchange. Typically they are part of broader, city-wide open data publishing efforts including the police data. Companies like Socrata can provide a unified interface to both the city department staff that produce the data and the citizens that consume it. Oakland, Chicago and Seattle are examples of cities providing rich, open data portals including police crime reports.

OakCrime.org is one example of a consumer of such public data. OakCrime.org takes data directly from Oakland Police Department’s public data interface and, using an open, shared code repository, provides it to Oakland citizens in forms useful to them. For example, through community policing activities like Neighborhood Councils, this data is published to support regular neighborhood meetings.

Of course, once available via a public API, commercial concerns are also free to capture this data and attempt to add value to it.

Private police data

Police IT vendors such as Motorola Solutions, TriTech/CentralSquare, and Lexis/Nexis sell long-term, multi-year contracts to police departments for services such as dispatch (911) call centers, incident and arrest record management, mobile data entry for officers, analytics, etc. As a by-product of this relationship, these vendors often provide a public-facing facility. For example, Oakland contracts with TriTech Software Systems (tritech.com, now part of CentralSquare.com and previously know as Omega Systems) for multiple police IT systems. TriTech.com provides the CrimeMapping.com interface showing a subset of the incidents occuring in Oakland.

As these various channels of data make their way through the Web, it is easy for them to become confounded. We will consider a source of police data a public data resource if it is provided directly by a government agency, and the data can be accessed both by spreadsheet and map browsing tools and also downloaded via CSV files or an API. Private provide commercial data resources, and typically provide only data browsing, without any ability to export the data.

Comparing the two paths

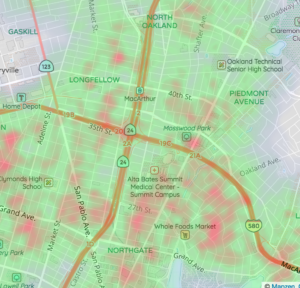

In two separate analyses, covering incidents in April 2013 and January 2014 of data provided by Oakland Police Department via its public data resource in contrast to that provided by CrimeMapping.com demonstrates that the data from this private vendor is less complete and “dumbed down.” This seems due to multiple causes, ranging from variations in police department data standards all served by the same IT vendor, to the small role public data plays in negotiation of the larger police IT vendor contracts.

Oakland’s experience is far from unique. As SpotCrime’s Colin Drane put it back in 2013, “Police departments contract with a vendor and give them preferential access to very important public data.” Or take it directly from an IT vendor, William Kilmer (then PublicEngines CEO, before PublicEngines was acquired by Motorola), “People look at our website and see that obviously as a public-facing manifestation of the law-enforcement data. But our primary mission is really to help law-enforcement agencies unlock the power of their own data for their own analysis.” Adam Hochberg, May 22 2013

Police Data on the WWW

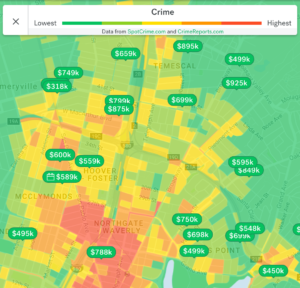

Once the data is in the hands of the police IT vendors, it becomes available for sale as “third-party” data. The IT vendor may share it with the citizens in the community, but that is only one audience for it. A good example is provided by the “crime” layer shown by the real estate data vendor Trulia.com; cf. Figure 2. These maps attribute the data to both SpotCrime.com and CrimeReports.com. A comparison based on Oakland data from 2017 shown in Figure 3 suggests there can be significant discrepancies between data reported directly by Oakland Police Department versus that displayed by Trulia, as gathered by SpotCrime.com and CrimeReports.com.

If you live in an area Trulia shows as having more crime than reflected by public data, you have real interest in how these errors can depress your home’s value. (If you’re a realtor, you might have interest in those areas where there is actually less crime than Trulia shows.) But because the path of the data from the police department through third-party products is opaque, attribution of errors and correction of them is attenuated by the chain of vendors between the police and the citizens it serves.

Consider the Trulia disclaimer:

- Therefore, the crime data displayed by Trulia may contain information that is incomplete, inaccurate or outdated, and information available for one area should not be compared to another area, or assumed to be complete. This information is meant to be a starting point for evaluating neighborhood safety, and should not be the only factor used in selecting the right neighborhood for you.

Or the one from SpotCrime:

- The data made available here has been modified for use from its original source. Neither SpotCrime.com nor our data sources make any claims as to the completeness, accuracy or content of any data contained in this application; makes any representation of any kind, including, but not limited to, warranty of the accuracy or fitness for a particular use; nor are any such warranties to be implied or inferred with respect to the information or data furnished herein.

Recent dynamics and the future

Further consolidation in the data brokerage industry (cf. GovtTech, Andrew Westrope / April 22, 2019, Reveal, Miranda S. Spivack / January 23, 2017, and Adam Hochberg, May 22 2013 mentioned previously) has recently consumed Socrata, a leader in the publishing of civic data according to open data standards, acquired by Tyler Technology (TylerTech). TylerTech is another major police IT vendor. Because many police departments have been using Socrata as their public data publisher, there is reasonable concern that TylerTech will see competitive advantage in reducing the open access to data Socrata provides, in favor of private versions that police departments share with them.

These issues become more pressing because current information about basic features of police activity, at the level of incidents on maps for example, reflect only the beginning of data streams, among citizens, between citizens and their police department, with city oversight commissions, etc.

Consider the potential and perils surrounding “tip lines” for the public to provide additional information about specific incidents. These offer new potential for enriched police–community communication. Unsurprisingly, TylerTech and many other police IT vendors include citizen “tip” reporting products. Whether citizens are willing to share information about crime incidents with one another, with their local neighborhood council, and/or with their police department, will depend critically on transparency of shared data sources and mutual trust among those involved.

The growing network of privately owned surveillance cameras represents an even richer data exchange possibility, as recent concerns regarding Amazon’s Ring and Google’s Nest can attest. Again unsurprisingly, TylerTech and others include citizen camera registration products.

So we’d better get our act together, people, around the much simpler issues of sharing the basic facts of the policing activity happening to us and payed for by us. CodeForAmerica has a series of brigades across the country, where many of them are working on applications exposing their local police department’s data. Find the brigade in your area, find out what data your police provide, who in your city government is managing the contract for Socrata data, … Then, MAKE SOME NOISE!